Before getting to the heart of the matter, let’s explain to newcomers what a capital gain is.

Imagine that you buy CHF 100 worth of Apple shares, and a year later you decide to sell them for CHF 150. We agree that’s cool because you’ve just made CHF 50 profit, right?

Well that’s what a “capital gain” is.

You have invested a capital of money in the stock market, and this gain has made a capital gain (of CHF 50 here), which you get back when you sell your stock and get your capital back in cash.

One of the things we are most envied for in Switzerland (apart from chocolate, cheese, watches, and everything else) is that our tax system does not tax these capital gains. In our case with the Apple share, that means you get CHF 50 net of tax.

But, because there is a “but”, you can become taxable on these capital gains if you are considered a professional investor.

You tell yourself: “Phew, that’s not my case, I’m safe, as I’m a rookie investor!”

Don’t be so sure, because the Swiss tax authorities will decide whether you are a private or professional investor, depending on the circumstances in which these capital gains were realized.

And so, if you come to be treated as a Swiss professional investor, then you will have to pay income tax on the CHF 50 that you earned with your resold Apple shares.

The 5 criteria to be met in order not to pay Swiss capital gains tax

The Swiss tax authorities, also known as the AFC/ESTV, describe in their circular no. 36 (here in German) the following 5 criteria which, if all are met, make you a private investor (and therefore exempt from capital gains tax):

1. The securities sold were held for at least 6 months

2. The total volume of transactions (sum of all purchases and sales) does not represent, per calendar year, more than five times the amount of securities and holdings at the beginning of the fiscal period

3. The realization of capital gains from securities transactions is not necessary to replace income that is missing or has ceased in order to maintain the taxpayer’s lifestyle. This is normally the case when the realized capital gains represent less than 50% of the net income for the tax period in question.

4. The investments are not financed by borrowed funds or the taxable returns on assets from securities (e.g. interest, dividends, etc.) are higher than the proportional share of passive interest.

5. The purchase and sale of derivatives (in particular options) is limited to the hedging of the taxpayer’s securities positions

If you follow the Mustachian method of investing in ETFs that I apply for my savings (summarized on this link), you shouldn’t have anything to worry about since my approach makes that:

- I keep my securities for several decades without reselling them (i.e. more than 6 months), because stock market trading is the best way to lose money, and to pay more taxes than necessary

- I don’t buy or sell more than 5x what I already have invested (the day it happens, it’s that I earn too much money :D). To break this rule with my current situation (about 200kCHF on the stock market), I would have to buy or sell for 1MCHF of securities (200 x 5). There’s margin!

- I am not living on the interest and dividends of my current returns. That’s one of the rules I might break when I’m FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early), but again, it’s not sure because I would be living on a mix of capital gains AND dividends (and not only on capital gains)

- My ETF purchases are not financed by someone else (that could be cool — if you ever have too much cash, just let me know!). Likewise, my interest or dividends are more important than passive interest, since I don’t pay any passive interest. Passive interest in this case is the same as if I had borrowed money (to invest) on which I pay interest (as with any private debt or credit)

- I don’t buy derivatives because I don’t understand what’s in them

The case where you can be considered as trading in securities professionally is if you are exploring (as I am) investing in value (more info here).

It is rare, but via this mode of investment, I sometimes keep my securities for less than 6 months. It is therefore an interesting case to which I will have the answer in 2021 (I will update my article from then on). But I think there is little chance that it will change my status because it only represents a few hundred CHF of capital gain on a total portfolio of about CHF 200'000. And also, because my shares in value only amount to CHF 30'000 in total, the rest being my ETFs that I keep for the long term.

Afterwards, as everyone says, the final decision is up to the good judgement of the person who controls your taxes. If the latter uses his common sense, I should be safe for life unless I decide to move to 50-80% shares in value investing on the total of my portfolio.

“But how can the Swiss tax authorities evaluate these criteria in reality? “ I hear you ask.

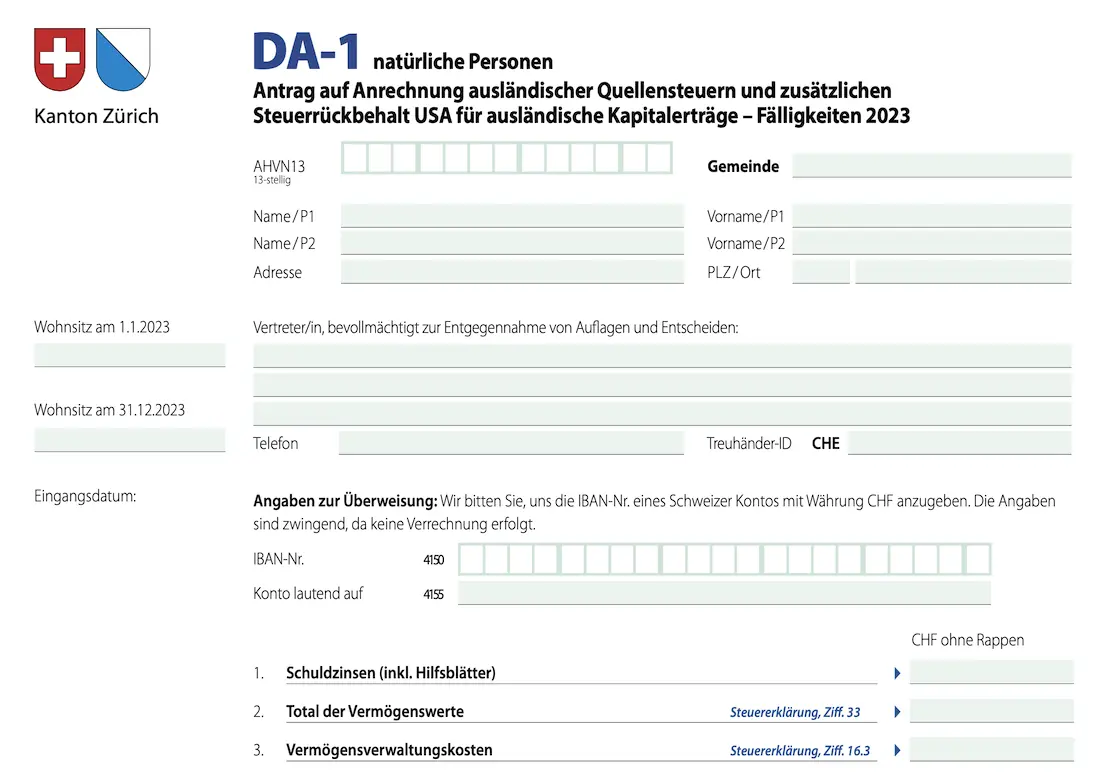

In fact, the Swiss tax authorities can evaluate these parameters because you have to declare any purchase or sale of securities (shares or bonds) in your Swiss tax return. Since I know this is a subject you love (not!), I have created a step-by-step guide to filling out this part of your tax return in this article.

Next, let’s look at the taxes on the dividends you’ll receive when you buy your first investment securities to put your money to work while you’re doing something else.