As a human being, I’m full of paradoxes. And until this interview, there were many paradoxes related to financial independence and the FIRE movement that I couldn’t unravel due to a lack of knowledge. Particularly in economics, which I didn’t study during my school career.

How about an example? Is it possible to achieve long-term stock market growth without burning down the forests you love so much?

And another? Wouldn’t degrowth (i.e. intentionally reducing economic output) be more in line with a frugalist vision of the world?

Meeting with an internationally renowned economist

It was through various podcasts that I came across Jean-Pierre Danthine. Who better to answer such questions than an economics professor, who is also former President of the Paris School of Economics, AND former Vice-President of the Swiss National Bank?

You’d think that talking to him would bore you to death and you’d understand nothing… but on the contrary, what I liked about him is that he explains and popularizes economics in a way that’s intelligible to the average person. Phew!

And above all, what attracted me most was his success in talking about economics, capitalism, planetary limits and so much more, in a scientific way only, and never in a political way!

Let’s go with the interview.

Jean-Pierre Danthine’s presentation

MP: “Can you tell us a little about yourself, your background, and what you’re up to these days?”

My name is Jean-Pierre Danthine. Basically, I’m a professor of macroeconomics and finance. I began my career by teaching for a few years at Columbia University, before joining HEC Lausanne. Initially, I taught mainly macroeconomics, but my research has always been at the interface between macroeconomics and finance. So, quite naturally, I gradually turned more towards finance, also in line with the needs of the faculty.

I stayed at HEC Lausanne until the end of 2009. At that point, I was appointed to the Swiss National Bank (SNB). I first became head of the third department, then was appointed Vice-President, in charge of the second department. This led to my appointment to the Executive Board, the trio of technocrats responsible for steering the country’s monetary policy. I held this position until mid-2015.

Then I became President of the Paris School of Economics, a position I held for six years, until around 2021. At the same time, I also joined the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, where I created and directed a center called Enterprise for Society, or E4S. I ran it until mid-2023.

Since then, I’ve been Honorary Director of the center. But I’m still fully involved in thinking about its objectives, its mission and the resources it can mobilize. This center, which brings together EPFL, the University of Lausanne and IMD, aims to help society make a successful transition to a more resilient, inclusive and sustainable economy.

Capitalism

MP: “What book would you recommend to understand both the positive and negative aspects of capitalism, without any political bias?”

The answer is that I don’t know any. Obviously, the real question is: what do we mean by capitalism? I have the impression that, for many people, it covers very different things. As far as I know, there is no accepted definition, at least not from the point of view of economic theory. In fact, it’s a term that’s not really used in that context.

So, capitalism… For some, it’s synonymous with neoliberalism. For others, it’s simply a market economy. Some will insist on asset ownership, on individual property. But I don’t have a definition of capitalism that says that’s what it is.

I think that, for my part, I would say that at the heart of capitalism, there is indeed this notion of ownership. But this ownership doesn’t have to be individual; it can very well be collective. The idea is that the owner takes care of what he owns, and that in a world of owners, we all end up better off.

If we adopt a very broad definition, the owner can be the community, a group of people, a foundation… It can take many forms. Another way of looking at it would be to say that capitalism is a form of economic organization that aims to preserve capital — that’s the idea behind the etymology of the term. And on that, I quite agree.

But for me, capital isn’t just physical capital — machines, buildings, etc. — it’s also human capital. It’s also human capital, social capital and natural capital. So if I say that capitalism is a system that aims to preserve, even develop and grow, our collective capital — be it physical, human, social or natural — then yes, I consider myself a convinced capitalist.

But I don’t know of any book that clearly explains the strengths and weaknesses of this vision of capitalism. So no, I don’t have a very formal answer to that question.

MP: “Can we have a capitalism that doesn’t destroy the planet AND doesn’t make us malicious to each other?”

I’ve already answered that question, in a way, by saying that my vision of capitalism is precisely one that seeks to maintain natural capital. And in a world like today’s, where GDP is rising, where wealth is increasing, where physical capital is growing, where human capital is progressing — insofar as it can be measured — social capital, on the other hand, is more problematic. The world is becoming increasingly polarized, so there are undoubtedly questions to be asked at this level. Even if, in reality, we don’t have very clear measures for assessing it.

What we do have very clear measurements of, however, is that natural capital, for its part, is in decline, and here we have a real problem, which goes against, I would say, my definition and vision of capitalism.

Why do we manage to naturally develop physical capital, and even human capital? Because there, interests are relatively well aligned. In the case of natural capital, however, this is not necessarily the case. There are externalities, or what we call “missing markets”.

If capitalism relies on the existence of markets to function properly, these markets must exist. But there is no market for preserving nature in 50 years’ time. There is no “natural market”. So, mechanically, I’d say that capitalism in this area needs to be supplemented. The market needs to be accompanied by intervention — to ensure that this capital is also preserved. Today, we’re not there yet.

Does capitalism make us malicious to each other? It’s an interesting question. If we go back to Adam Smith — who is, basically, one of the great thinkers behind economic thought in the XVIIIᵉ century — he championed this idea of the invisible hand, an extremely powerful intuition, which was, incidentally, confirmed by some very important theorems later on.

But in this vision, within the framework of competition or the market, producers and consumers are partners. There’s a form of implicit cooperation. And I think that’s what we’re missing today, in a capitalism that has perhaps gone beyond what we would like it to be, and which is perhaps insufficiently regulated.

What underlies a lot of what I’ve just said is that when there’s no market, there has to be another form of regulation. It has to come from the community, the state, or some other representation of the community. Insufficiently regulated capitalism can indeed lead to antagonism, polarization and the feeling that the system makes us malicious towards each other. For me, this is a perversion of a well-understood capitalist organization.

Stock markets

MP: “Why do we say that markets always recover?”

I think the real answer, without going into detail, is that the market follows the growth of the economy. If you take an indicator like total market capitalization divided by global GDP, you’ll get something that statisticians would probably call stationary.

And then there are big fluctuations. At times, we see stock market booms, then crashes. The real economy, on the other hand, is much more stable. But over the last 200 years, it has grown steadily. So, if we make the connection, it means that, over the long term, the market follows the development of the real economy. And as long as we remain in a growing real economy, if we’re patient enough, we can expect the market to eventually recover.

The reality is that this recovery can sometimes take a long time. There have been 20-year periods when the stock market made nothing. It’s happened. So, if you’re very patient — let’s say 50 years, since the Industrial Revolution — you can say that markets always recover in the end.

After that, it’s not necessarily something very comfortable for someone my age, for example. My horizon may not be as long as that. But that’s the reality.

MP: “Why are there bear and bull periods? Can you explain it as if you were talking to my 15-year-old child?”

I think the key point is that the level of the market depends on what the economy is producing today, but above all on what we anticipate it will produce in the future. And here we enter a field of uncertainty. We anticipate: will this company continue to develop well in a year’s time, in five years’ time? Will a company in difficulty today be able to recover?

So we focus a lot on a horizon of one, three, five or even ten years.

Since we don’t know what the future holds, sometimes we can be optimistic… and sometimes, much less so. What happens, in fact, is that when you’re in a climate of optimism, you tend to stay optimistic. And when the mood is pessimistic, you tend to stay pessimistic.

So markets have this propensity to go through phases: phases of optimism, of bullishness. And then, all of a sudden, it’s a bit like a balloon… something punctures it, and it deflates. Then we realize that we’d all gotten a little too excited about something we thought was fantastic… which, in reality, wasn’t so fantastic at all. Worse still, we discover that something has happened to change all that.

Take a concrete example: everything seemed to be going well, and then a gentleman named Trump starts making catastrophic decisions. We thought everything was running smoothly, and then overnight, this gentleman makes decisions that, for everyone else, will instead create instability. And so, the market turns bearish.

MP: “Why do we say that markets always “go up”? How can we be “sure” of this in economics?”

It depends a lot on the growth of the economy. Still, we’re in a world where we’re beginning to wonder about this fundamental growth.

These questions are, for example, linked to the fact that today, if we really want to look reality in the face, we can see that the globalization factor — which was linked to a certain trust that people had in each other — is changing.

We spoke earlier of malice, but for a long time, there was this basic trust: we could each specialize in our own field. This meant accepting that we couldn’t do everything on our own, but that by working together, on a global level, we could achieve a much more effective result than if each country tried to do everything on its own.

Since the 80s and 90s, this phase of globalization has been extremely positive for economic growth. Today, however, we are witnessing a reversal: for geopolitical and ideological reasons, we are entering a phase of fragmentation. We’re gradually unravelling mechanisms that we know have been highly favorable to growth.

Logically, this should make growth less dynamic, even leading to phases of stagnation… and perhaps even decline for a time.

And of course, this would have an impact on the markets, for the reasons I mentioned earlier.

MP: “What impact does taking environmental issues into account have on this statement (the fact that the economy is still growing)?”

That’s good, because actually, in the previous question, I was talking more about a short-term perspective, with deglobalization. If we take a longer-term view, we’re talking about environmental issues.

There are in fact two extreme scenarios — and we’ll probably end up somewhere in between. The first is a business-as-usual scenario. In this case, global warming, climate-related disasters, loss of land productivity… all these will impact on our ability to generate growth in the future. This could lead to stagnation, or even decline.

Conversely, the other scenario is one where we decide to take the bull by the horns and tackle global warming, climate catastrophes, biodiversity loss and declining land productivity. We know that technology will help us in this transition… but it won’t help us all the way. Not completely.

Which means that, in some cases, we may have to curb our desire to consume a little. And that could have an impact on measured growth — on GDP, in short.

L'Étang de la Gruère <3 — if you know of any other places like this in Switzerland, I'd love to hear from you! (photo credits: j3l.ch © Gerry Nitsch)

Let me give you a concrete example: mobility, with aviation. Today, this sector is booming. It has taken off again, and is still going strong. We’re even back above pre-Covid levels. If you look at Boeing or Airbus aircraft production figures, it’s impressive. So are the figures for airports. Except that all this is totally incompatible with respect for planetary limits.

So if we really decided to face the issue head-on, it would mean accepting that we’ll be flying less.

There are different ways of achieving this. But if we took the right decisions, we’d be flying less. This would mean that the aviation sector — Airbus, Boeing — would produce fewer aircraft, and generate fewer salaries. Airports? The same thing. Of course, the money would undoubtedly go elsewhere in the economy. But a whole sector of the economy would stagnate or even shrink.

I have to say I’m not a great believer in that — unfortunately. But, theoretically, we can see that the impact could be negative on growth.

Economic growth

MP: “Does economic growth necessarily imply material consumption? What is the link between the two (if there is one)?”

The first thing to understand is that growth figures are essentially linked to our ability to do better with the same resources. In other words, growth could come from working more and more, or using more and more machines to produce what we want to produce.

It’s true that if we always had more machines, there would be growth — that’s what economic theory says. But that would be absurd. Because machines depreciate. If you have too many machines, they end up costing a lot to maintain and replace. It’s a bit like with the roads in Valais: if you build too many, after a while they become too expensive to maintain. Then we say we’ve gone too far.

It’s the same for the economy in general. If you have too many machines, it no longer makes sense. And on a macroeconomic scale, we can see that in developed countries, or in those that have reached a level of development known as the “steady state” — a certain equilibrium — growth no longer comes from having more material things. It comes from having better ideas.

And when we understand this, we also realize that consumption, in terms of GDP, is increasingly immaterial. And that the future will undoubtedly go in this direction. We already have a lot of computers — do we need twice as many per person? The answer is no. We’re even tending towards a concentration of equipment. We’ve gone from a time when many people had two cars, to a time when, for many, that no longer makes sense.

Yet incomes continue to rise. And these incomes are increasingly used for immaterial expenses: culture, travel, personal care… things that are not material.

So, the answer is no: economic growth does not necessarily imply increased material consumption. We’ve probably even reached an absurd point in our developed countries, where material consumption has become so sacralized that we want more and more of it — even though we can see that it adds nothing to our satisfaction or happiness. It’s a cultural problem.

From an economic point of view, there’s nothing to say that having two iPhones will make you happier, or that you absolutely have to buy a new iPhone every year. It just doesn’t make sense.

So no, growth doesn’t necessarily mean more material consumption — that’s quite clear.

Now, how do we change the pace? Maybe your movement is one way: telling ourselves that we can be a little more frugal, and realizing that we won’t be any more unhappy as a result. Maybe we could even work a little less, or use our money differently. And all this is perfectly compatible with economic growth. It’s even totally compatible with economic theory, which has never said that the aim is to maximize growth.

MP: “What’s your take on degrowth? Put another way, is growth a bad thing?”

It’s true that the degrowth movement starts from a different vision. It’s not a question of “what do we want to achieve”, but rather “what must we do to respect planetary limits”. It’s the idea that resources are limited. Only a slightly utopian economist would believe that growth could be infinite.

But I’ve answered that a little: growth isn’t necessarily linked to material resources. It also comes from our ability to do better with the same resources, or even with less. So the idea that “finite resources equal impossible growth” isn’t necessarily true. The real question is: do we have to respect planetary limits? And here I come back to what we said at the beginning: we absolutely must preserve our natural capital, for ourselves and for future generations.

Today, technology doesn’t allow us to do this with “business as usual”. So something has to change. There’s a pessimistic view that says the only solution is degrowth — because growth would mean too much consumption, too much pollution. So if we decrease, we’ll be moving in the right direction.

I think we need to be a bit agnostic on this. For me, the objective is not to decrease. The goal is to respect planetary boundaries. You have to be intelligent, stop consuming material goods absurdly, stop thinking that you always have to work more to earn more and consume more.

Will we ever get there? I don’t know. But what is certain is that respecting planetary limits is an imperative. And if we do it intelligently, I think we can continue to grow — at least, if we measure that growth correctly. The aim is not to shrink. The aim is to respect planetary limits, to be intelligent, to preserve our level of well-being, and to enable future generations to enjoy the same level of well-being. That seems obvious to me.

The objective is not to decrease. The objective is to respect planetary limits, to be intelligent, to preserve our level of well-being, and to allow future generations to benefit from the same level of well-being.

Will this lead to degrowth? I think not, in the long term. Will there be phases of slower growth? If we really want to be serious about respecting planetary limits, then yes, undoubtedly.

I gave the example of aviation: if we fly less, there will be an impact. So yes, there could be phases where growth will be slowed, or even negative. In fact, even today, growth is sometimes negative — so a fortiori, this could also be the case in this context.

Investment performance and diversification

MP: “Is it still possible to expect an average annualized performance of 7% from a global ETF, while respecting global limits? Why not? And if not, what return (%) can we expect?”

What I’ve just said implies that I won’t have a very precise answer to give. I think that if we could count on an average performance of 7%, as we’ve seen in recent years, this would probably not be a good sign. It would mean that we’re not doing what we need to do to respect global limits. Precisely because respecting these limits should, in some areas, mean slowing down.

Why would this be? Because the technology we need isn’t yet available. That’s why. But it’s also possible that we won’t do anything, and that we’ll continue to have this type of performance for some time to come.

So what’s going to happen? We’ll have global warming, disasters, major population movements, less and less productive land. All this can only lead to lower yields in the long term.

So I’d say we’re in a world where we’re facing a fork in the road. Whether we go left or right, in the medium term, I wouldn’t bet on yields comparable to those seen over the last 30 years, for example.

Now, what figure should we give? I don’t know. Because it will depend on our ability to be intelligent in the way we manage all this.

It’s not just a question of technology. Yes, there’s technological innovation that can help us, but there’s also the way we govern it all, the human management, the general governance. And here, we can either do it the stupid way, or try to do it a little more intelligently.

MP: “For the average Swiss, I’d recommend investing in a World ETF to be as diversified as possible (risk reduction), while getting the best possible performance.

What’s your economist’s view of such a portfolio, including environmental issues?”

My point of view as an economist — and more precisely, as a professor of finance — is very clear: maximum diversification is the only thing an individual investor can really do.

Maximum diversification is the only thing an individual investor can really do.

Don’t try market timing, don’t try stock-picking. Maximum diversification is really the right starting point. That’s the basic strategy we should be building on.

ESG investments, good or bad?

MP: “Are ESG ETFs a good investment vehicle (from an economic point of view)?”

Yes… I’d like to say yes, but today, in fact, we’re not very convinced of the way ESG ETFs have been implemented. So it’s a bit hard for me to say that ESG ETFs are absolutely preferable to World ETFs.

I think that, particularly if you’re environmentally sensitive, it might be wiser to set up a World ETF for, say, three quarters of your portfolio. And on the remaining 25%, target investments that are really going to have a positive impact on the transition to a new form of economy. But it’s not easy to do, I have to admit. And I find that, from this point of view, intermediaries — who should be helping investors like you and me — aren’t doing enough yet.

It’s a bit of a vicious circle: these intermediaries say they’re not offering more options because there isn’t enough demand yet. On the other hand, they also have a fiduciary duty: their objective is to meet the expectations of their customers, who today are primarily interested in returns. Many people would be willing to invest in a more sustainable way… as long as there were guarantees that this would not harm their return. And today, it’s very difficult to guarantee this, for obvious reasons.

The world is changing. We’ve seen it: a number of ESG ETFs, for example, have excluded the oil and fossil fuel sectors. But when the price of fossil fuels rose sharply, these ETFs found themselves in trouble with their clients. The same applies to the arms industry, for example.

So it’s not obvious at all. And I don’t think intermediaries have yet found a truly convincing solution that would enable investors who don’t want to spend all their time on it, to make choices that really make sense.

That said, there is one question that needs to be asked. Today, we live in an extremely uncertain world. And the question is: as much as the strategy you defend — being 100% invested and then forgetting about it — has been very valid in the past, today we may be faced with a real paradigm shift. Which might be worth having a small, much safer investment pocket on the side, just in case things go really wrong.

And here, I don’t have a ready-made answer. It’s a very difficult question. Because the problem we face today, as clear-sighted investors, is that there are huge risks… which may well never materialize. What we call low-frequency risks.

And how do you protect yourself against these risks? The problem is that if you try to protect yourself from them, and they don’t materialize, you’ll lose out. And you could be for a very long time, precisely because these risks are so rare.

So I think it’s a question you have to have somewhere in the back of your mind. And it can lead you to think that certain recommendations that were very pertinent in the past - and that have worked well up to now — might not work so well in the future.

Divestment strategy?

MP: “Is the divestment strategy (exclusion of certain industries/companies) effective in supporting environmental objectives, as a private investor?”

The answer is no. In fact, there are very few examples where a divestment strategy has actually proved effective.

If, behind this strategy, there’s the idea that we’re going to “turn off the tap “, that when we invest we’re giving money to a company to do things we don’t like, and that by stopping investing, we’re going to prevent it from continuing… well, it doesn’t really work like that.

Because when you sell, someone else is bound to buy. And even if, in extreme cases, a company were to find itself limited in its financing via the stock market, it would still have access to other sources: private markets, bond markets, bank loans. There are plenty of alternatives.

For such a strategy to have any real impact, all investors would have to agree. But that’s totally illusory.

The reality is that what we’re seeing is that disinvestment strategies are mainly a way of making ourselves feel better. You feel better when you use them, but they are not effective on their own. And they often lead to unbalanced portfolios, with risk-taking different from what it would normally be.

Disinvestment strategies are mainly a way of easing one’s conscience. They are not effective in themselves.

They are not the right way to act. The best approach would be to join an investors’ club that takes concrete action: by taking part in board meetings, intervening at shareholders’ meetings, influencing company strategy to steer it in a different direction.

An individual investor can’t do that alone. It has to be done collectively.

Financial education and environmental issues

MP: “How can education in personal finance (budgeting, saving, investing, etc.) help solve environmental problems?”

I think it’s important to have a minimum of financial education. In particular, this fundamental idea of investment diversification is absolutely essential. It’s part of a form of humility: we know so little that we have to accept diversification.

And it requires a certain level of education, especially given the prevalence of scams and misleading advertisements. We regularly see people who have put all their eggs in one basket — a basket often offered by someone who isn’t necessarily honest, or even competent, but who knows how to express himself very well. Avoiding such situations is obviously crucial to your financial health.

If you’ve managed your finances badly, the end of the month will come first. But if you’ve managed your affairs well, you may be in a position to think more about global issues — including the end of the world.

And then, once you’ve built up a healthier financial situation, you’re probably in a better position to open up to other issues, such as environmental problems — beyond mere financial survival.

It’s often said that there’s a conflict between “the end of the world” and “the end of the month”. If you’ve managed your finances badly, the end of the month will take precedence. But if you’ve managed your affairs well, you may be in a position to think more about these global issues — including the end of the world.

Frugality vs. growth (to achieve financial independence)

MP: “What do you think of the paradox of financial independence (FI), which encourages thoughtful consumption (no unnecessary material accumulation, frugality and the pursuit of a happier, richer life) while relying on capitalism and the stock market to finance a free life (= not having to work for money, not “not working / doing nothing on the beach”) — where growth is necessary?”

I think growth is useful, of course, it makes things easier.

But with a standard of living like the one we have in Switzerland, we can organize ourselves very well with minimal growth. In fact, we’re already in that situation to some extent. Per capita growth in Switzerland is not very high, compared to the 5, 7 or 8% we’ve seen in China, which is still a developing country.

I think the important point is that we can organize an economy — a capitalist, market-based economy, with stock market operations — that is perfectly compatible with modest growth. And it’s absolutely not incompatible with more thoughtful consumption, with frugality.

It might be a slightly different economy from the one we know today, but it’s definitely doable.

Again, I’m making a distinction between the common view we have of capitalism — which is often misunderstood — and the view I’m proposing, which is much closer to economic theory. It’s a means, a dream, a result of our imagination, of our ability to do better.

But it’s not a goal in itself. The goal is precisely to live a happier, richer life.

MP: “Is passive income from investments (one of the pillars of the FIRE movement) incompatible with the environmental challenges we face?”

Passive income… you mean annuity income, as it were? Is that what you mean? Rather than income from work?

Yes. So no, I don’t think it’s incompatible. Now, it’s true that not everyone can live on an income from work. Some people have to work. And I think that’s an important point, because in a comfortable society like ours, there’s perhaps too much of a tendency to believe that money falls from trees, that all you have to do is help yourself.

No. People have to work. Value has to be created. It doesn’t grow on trees. So I think we need to keep a certain balance. To imagine being able to live on passive income alone for the rest of your life is to depend on the work of previous generations. It’s all very well to benefit from it, but it’s not sustainable on a large scale.

I think that as much as possible, everyone should contribute to the collective effort of creating value for society. Of course, everyone has his or her own dispositions, skills and characteristics. But contributing can also mean making capital available, because you’ve been particularly frugal, for example. Making capital available is also a form of contribution. So it’s not just about work, it’s also about capital and financial resources.

But I think we’ve reached a period where it’s perhaps a little too easy to assume that everything will continue to go well, even if we don’t contribute. We’ve become a little complacent with this idea. And I think we’re entering a phase where this will no doubt be called into question.

We sometimes think that simply taxing the rich will solve the problem. But that’s not true. We need continuous value creation. And in today’s world, which is a little less cooperative than it used to be, some of the advantages we enjoyed in the past are no longer there. This should encourage us to be a little more proactive, to make sure that everyone contributes to this collective effort.

MP Notes

I’m a materialist AND a capitalist!

When I saw the film “Minimalism” (available on Netflix), I was struck by economist Juliet Schor’s commentary:

We’re too materialistic in the everyday sense of the word, and not materialistic enough in the true sense of the word. We need to be true materialists, i.e. to really care about the materiality of goods.

Since then, I’ve considered myself a materialist. It’s provocative, and sparks interesting conversations in my circle.

After my discussion with Jean-Pierre Danthine, I can now add to this statement: “I’m a materialist AND a capitalist.”

Because if we want our economy to be sustainable over several hundred years, every business owner (including his land and his use of natural resources) must cherish and take care of his capital.

This goes very well with my frugal approach to life, where you make conscious, quality purchases. Purchases of tangible or intangible goods (because even intangible goods have an impact on nature) made to last.

Bye bye Temu and Shein, and hello frugal lifestyle!

And all this reasoning is not incompatible with economic growth and increasing people’s happiness, quite the contrary! I think I’ll be continuing the blog for a while (no, no, I didn’t doubt it, but this reminder with a global perspective is welcome).

Do you know a good book on capitalism?

I find it hard to believe that there isn’t a good book on capitalism that doesn’t start getting political right from the preface… well, I didn’t do much research myself, I was counting on Jean-Pierre ;)

In any case, if you have such a book in store, contact me by email or via the comments with pleasure!

Producers and consumers are partners!

Speaking of global perspective, I really liked the part where Jean-Pierre talks about economic relations.

Any business should add real value, as if it were a partner to its consumers, and not an extractor wishing to maximize its profits without thinking too much about the consequences (ethical, environmental, integrity, etc.), in a smoke-and-mirrors mode.

I’m thinking here of ad salesmen such as Meta, and to the Tiktok, Temu and Shein again.

If I take my blog as an example, it resonates with my long-term strategy vs. accepting the requests for ad placements or crappy links I get every day… and yet there’d be a ton of cash to be made, and I can tell you I’d already be financially independent. Well, no, not really. Because I don’t think I’d really have any readers left, and such a short-termist approach would have sunk my blog a long time ago.

Two buddies who have figured out a lot of simple things AND terribly effective when applied over the long term and at all personal and professional levels (photo credits: CNBC Television)

Another example is my first real estate deal club, which I’m currently setting up. One of the founding principles is to align my own interests as closely as possible with those of the investors. I’m not inventing anything, I’m just borrowing the precepts of mentors such as Warren Buffett (invest your own money alongside shareholders in “skin in the game” mode), Charlie Munger (“show me the incentives and I’ll show you the result.”), and Jack Bogle (Vanguard doesn’t seek to maximize profits, but to reduce costs for its investors, as they are the owners of the company). So it simply means no unnecessary management fees, and a stake at least as big as each investor.

Markets always go up

I recommend reading this article if you want another perspective on the subject.

Oh, and a necessary reminder: markets always go up for the index investor (as with the VT ETF), not for the stock-picking investor. Indeed, a VT ETF benefits from automatic self-cleansing thanks to its intrinsic indexing system: bankrupt or declining companies are removed from the index, replaced by better-performing ones.

Growth and planetary limits

I agree with Mr. Danthine when he says that money not spent on materials would go elsewhere in the economy, and growth would not stop.

I’m more optimistic than he is (rightly or wrongly, time will tell). Whether it’s nature, a law or a new environmental market system, human behavior adapts to constraints. We saw this clearly during COVID.

If we could no longer fly tomorrow, I’m not sure that the slowdown in growth would be that great. Most of it would be transferred. Private individuals will look for and find other ways to enjoy their leisure time. Ditto for business travel; companies will have more cash to reinvest in more useful things than business trips that could be made via Zoom.

Again, this is just one hypothesis (from an optimist) among many. Time will tell who’s right. And as usual, we’ll certainly be somewhere in between.

Degrowth, not necessarily a solution

Without politics nor dogmatism, I loved this sentence: “You have to be a bit agnostic about it. The objective is not to decrease. The goal is to respect planetary boundaries. You have to be intelligent, stop consuming material goods absurdly, stop thinking that you always have to work more to earn more and consume more.”

Obvious? One still had to have the intellectual baggage to explain it so concisely.

7-8% return?

Maybe I’m too optimistic (or less armed with knowledge of macroeconomics), or maybe I’m younger and still too idealistic, but I don’t necessarily think that growth is going to fall as much as Jean-Pierre Danthine predicts.

My vision tends more towards a redirection of wealth towards more intangibles, when the majority of the population realizes (forced by nature reclaiming its rights or some other environmental law forcing a change in behavior) that over-consumption is neither healthy nor desirable for any human, and that there are other ways to be happy — in the long term (and not on dopamine shots scrolling to infinity!) More sustainable ways. And these things will generate economic growth.

Just to be clear: no, it won’t be easy to maintain some growth while respecting the Paris Agreements. But if we reallocate capital intelligently and rely on the green transition as a driver of innovation, there’s no reason why that growth can’t remain solid, or even be strengthened in the long term.

Let’s talk about it again in 50 years!

Diversification, diversification and diversification (of your investments)

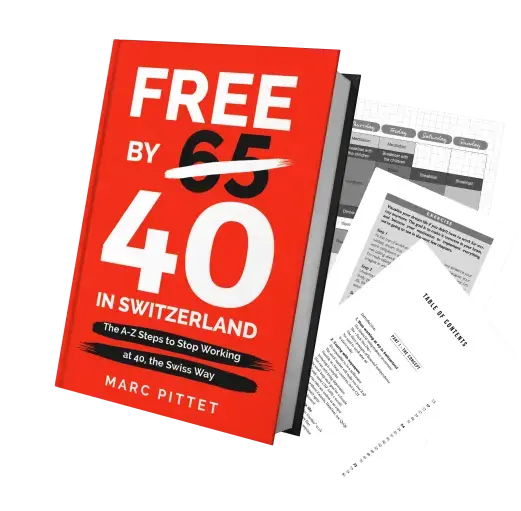

If you still needed “official” proof from a “real” economist (vs. a random Swiss blogger) to confirm everything I say in:

- this article on how I’d invest CHF 10'000 if I started from scratch today

- my book

- or my program that allows you to start investing in the stock market in a few weeks by understanding what you’re doing

… so here it is from a real, official economist: “Maximum diversification is the only thing an individual investor can really do.”

ESG and divestment, yes… but no!

I understand the intention behind ESG and divestment. But personally, I prefer to stay invested in all companies worldwide, through a well-diversified portfolio (or should I say through the one and only: the VT ETF). And using my time to make a real impact. This blog is one example. Others, once FIRE, choose to work in sustainable companies. And the bravest (or the least afraid?) jump into impact entrepreneurship with both feet.

My conscience grumbles a bit sometimes, but it gets over it. I want to act where it’s proven to work. Not just do what most people do to ease their conscience… when in the end, it doesn’t change a thing. Nada.

If you want more details on this subject, I recommend this article that is still valid today.

Conflict between the end of the world and the end of the month!

This quote really resonated with me about the raison d’être of this blog and all my related projects. I’m going to add it to my Ikigai:

I help you breathe financially at the end of each month, so you can invest your time where it really has an impact.

More clarity in my paradox of the rentier life

To become a retiree living off passive income, you have to work. You don’t get something for nothing. And once you’re financially independent (= FIRE), you continue to contribute to making the world go round by making your capital available. It’s also a form of contribution.

Summarized by Jean-Pierre Danthine: “it’s not just about work, it’s also about capital and financial resources.”

Or how to get more clarity on many of my human paradoxes.

I’d like to thank Mr. Danthine again for giving me so much of his precious time, as he’s working flat out on the end of the world :)

And you, what do you take away from this interview? (as usual, in constructive and apolitical mode, please)

Last updated: July 3, 2025